Illustrious tombs found in Madrid´s churches

Some of the most renowned names in the history of the capital lie not only in the Panteón de Hombres Ilustres and the city’s cemeteries, but also in its churches, which was where many of its most affluent citizens were buried up until the 19th century. Many of the tombs, sepulchres and cenotaphs that form part of this tour are works of art that are priceless in value, and others have witnessed the passing of time carved in stone. They can be visited at any time of the year, but be sure to check the opening times of the churches before going. By Ignacio Vleming.

Today, the incorrupt body of Saint Isidro Labrador, the patron saint of Madrid, lies alongside that of his wife, Santa María de la Cabeza, in the collegiate church that bears his name. It is said that after the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa, Alfonso VIII of Castile wished to visit Madrid to thank the town for its support. On his trip, he visited the mortal remains of this holy man. When the king saw Saint Isidro he was shocked, and not only because of his height (he was 1.80 m tall), but because he was identical to a priest who had guided them over the cliffs and reserves of the Sierra Morena during the conflict. To thank him, the Castilian king ordered a chest to be made, which, at the end of the 13th century, was substituted for that which can be seen today at La Almudena Cathedral, decorated with scenes of his miracles painted on leather.

We can honestly say that Saint Isidro’s chest was the most valuable work of art in Madrid before the 16th century. It was only once Henry IV of Castile began to frequent El Monte de El Pardo, followed later by numerous visits from the Catholic Monarchs, that Madrid began to emerge above other, up until then, much more important towns, including Toledo, Segovia, Burgos, and Valladolid.

The Vargas family were greatly involved in Madrid’s boom, which would result in the former Muslim Magerit becoming the permanent home of the Spanish Court. If Francisco de Vargas was secretary to the Catholic King, who coined the phrase “Go figure, Vargas” meaning “let it be done”, his son Gutierre de Vargas y Carvajal was one of the most influential theologians of the time and Bishop of Plasencia. It is his name that a chapel in the San Andrés Church bears, which was designed by Francisco Giralte in 1547 to bury the prelate alongside his parents. One of the masterpieces of the Spanish Renaissance, this monumental sculpture can be visited via a small cloister on Plaza de la Paja. The predominant use of estofado gold-leaf technique on alabaster is truly surprising, as is the brilliance of the angels playing musical instruments. The sculptor, who had previously worked alongside Alonso Berruguete, also crafted the spectacular polychrome wood altarpiece.

From this same period are the tombs belonging to a couple that, according to Castiglione, represented the two great virtues of the Renaissance: skill at arms and a vocation for the arts. While Francisco Ramírez, nicknamed “The Gunner”, was renowned for his victories during the war of Granada, his wife, Beatriz Galindo, was the tutor to Isabella the Catholic and her children, to whom she taught grammar and Latin. It is for this reason that she was known as “La Latina”, a name borne today by the neighbourhood in which she founded a hospital.

Said institution commissioned their alabaster cenotaphs in which their bodies were never laid to rest, and today are on display at the Museum of San Isidro. (The remains of the humanist lie at the Concepcionista Jerónimas de Boadilla monastery and those of the soldier were never found.)

During the Spanish Golden Age, the land beyond Puerta del Sol, which had only ever seen orchards and groves, became a stage for celebrities. Home to the open-air comedy theatres of La Cruz, La Pacheca and El Príncipe, where today the Teatro Español stands, it was also here—on the corner of Calle del León and Paseo del Prado—where the Talking Shop of Representatives could be found, i.e. the spot where many deals in the world of show business were closed.

This new neighbourhood, which became known as “Las Musas” or “Las Letras”, was called home by Quevedo, Góngora, Lope, and Cervantes. The author of Don Quixote was buried in the neighbouring Convent of Las Trinitarias in 1616, following his own wishes, as it was the nuns of this order who freed him from captivity in Algiers. This convent was also where his biological daughter, Sor Isabel Saavedra, lived. Here the young nun met a descendant of another illustrious figure, Sor Marcela San Félix, daughter of Lope de Vega and the actress Micaela de Luján, who also went on to become a celebrated writer like her father. Today they both lie in the church’s crypt.

As for Lope de Vega, or the “Phoenix of Wit”, he was buried at the Church of San Sebastián, which had a chapel belonging to the Brotherhood of Comedians of the Virgen de la Novena. His remains were transferred to a mass grave several years later and today their location is not known. Nor do we know what happened to the bodies laid to rest in the cemetery at the church’s entrance, upon which a florist’s stands today.

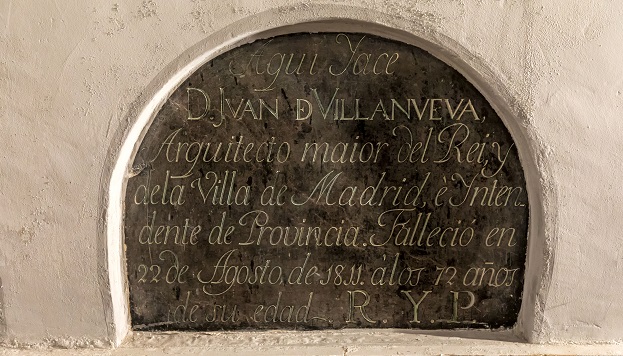

Legend has it that, one evening, José Cadalso visited the graveyard to attempt to exhume the body of his lover, the actress María Ignacia Ibáñez, known as “La Divina”. This tale crops up in the writer’s Lugubrious Nights, one of the most significant Pre-Romantic works in Spain. However, today it is thought that the author himself spread the rumour of his necrophilia to boost his novel’s popularity. We can’t leave the Church of San Sebastián without visiting the stunning Chapel of Our Lady of Belén. It is without a doubt the best-preserved corner of this house of worship which was first looted and later partially destroyed during the Spanish Civil War. Here lie two of the most important figures in Spanish architecture of the 18th century: Juan de Villanueva and Ventura Rodríguez —who is accountable for the chapel’s current design—and the reason why it is also known as the “Chapel of Architects”.

Despite their popularity in the Court, the luck of the chamber painters was very different. Velázquez, Felipe IV’s royal chamberlain, was buried at the Church of San Juan Bautista, of which today only its foundations remain in Plaza de Ramales. It was demolished in the times of José Bonaparte in an attempt to breathe new life into the old Madrid de los Austrias (Hapsburg Madrid), and when cemeteries were moved from the city. Today, a cross stands here at the place where the body of the artist who created Las Meninas once lay.

Goya, who painted Charles III, Charles IV and Ferdinand VII of Spain, died in Bordeaux and was buried there alongside his friend Martín Miguel de Goicoechea. In 1919, his remains were brought to Madrid thanks to the Spanish consul, Joaquín Pereyra. However, to much surprise, the artist was missing his head, which was most likely stolen by a doctor of phrenology. Today, the rest of his remains lie in the San Antonio de la Florida Chapel, which Goya himself decorated with frescoes that tell the tale of a miracle performed by the Lisbon-born saint after whom the chapel is named. As for the composer Tomás Luis de Victoria, he was buried at the Descalzas Reales Monastery, where he played the organ for more than 24 years, many of which were under the service of Empress Maria of Austria.

The remains of monarchs (including their heads), however, are not generally misplaced. The members of the Houses of Hapsburg and Bourbon lie in the Crypt of the Monastery of El Escorial, alongside queens who were mothers of other kings and next to the Pantheon of Princes and Princesses.

There are two exceptions to this rule: Philip V of Spain asked to buried at the Royal Palace of La Granja, a place where he sought sanctuary on many occasions due to bouts of melancholy, and Ferdinand VI of Spain who lies alongside his wife, Barbara of Portugal at the Salesas Reales Convent, where she planned to retire to if her husband passed away first. Today, this impressive eighteenth century building by Francisco Moradillo and François Carlie, is the headquarters of the Supreme Court, and the church is chosen by many locals to celebrate their marriage, thanks to its stunning staircase, perfect for showing off wedding dresses.

It’s worth heading inside to visit the mausoleums of this pair, who are remembered as being one of the most romantic couples in the history of the Spanish monarchy. They were sculpted by Francisco Gutierrez and Juan León based on a design by Francisco Sabatini, commissioned by Charles III of Spain. The two globes that sit atop the monument to the queen represent the universality of the Spanish monarchy.

The Church of Las Salesas is also home to the monument to Leopoldo O’Donnell, minister on various occasions during the reign of Isabella II of Spain. Crafted by the sculptor Jerónimo Suñol, who also designed the Monument to Columbus, which stands at end of the Paseo de Recoletos, this tomb evokes some of the most impressive works of the Renaissance. Although before we were referring to the Bishop’s Chapel, in this case, it is in the Alcalá de Henares University Chapel where the spectacular monument to Cardenal Cisneros by Domenico Fancelli can be found.

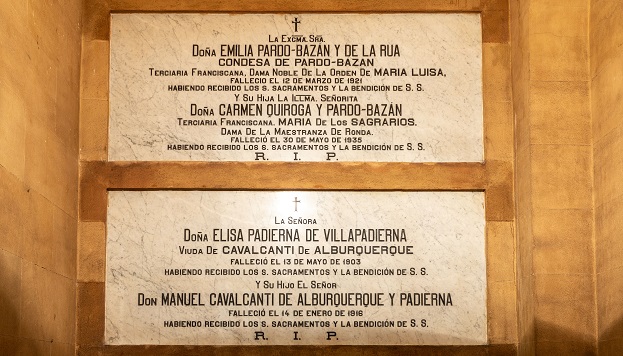

Despite church burials becoming less common in the 19th century, the Nuestra Señora de la Concepción Church, a Neo-Gothic building in the heart of the Barrio de Salamanca, was built with a crypt where the bodies of some of the most celebrated members of Madrid’s bourgeoisie and nobility lie, such as the writer Emilia Pardo Bazán, who lived between Pazo de Meirás and Madrid, and that of the journalist Torcuato Luca de Tena, founder of the weekly newspaper Blanca y Negro and author of the popular novel God’s Crooked Lines.

There is also the La Almudena Cathedral, which from the outset was designed to have a crypt for said purpose - the crypt today being the oldest part of the building. Access is via Calle Mayor after crossing Calle de Bailén. Marqués de Cubas lies in one of its Neo-Romanesque style chapels. The first architect of a building that was eventually built thanks to the relentless perseverance of María de las Mercedes. When before we spoke of the love between Ferdinand VI and Barbara of Portugal, we forgot to mention that we would have to wait more than one hundred years before seeing something similar: for Alfonso XII and this young girl, it was love at first sight. However, as she wasn’t a member of the royal family, she will spend eternity not in El Escorial, but below the Virgin of La Almudena. The Almudena Cathedral Museum is home to a mausoleum dedicated to the queen that was never used.

As we can see, many of the men and women that have appeared throughout this tour of Madrid’s churches were greatly influenced by genius, obsession, fame, and power. Writers, architects, artists, saints, and monarchs who went against the grain. This is also the story of Doctor González Velasco, who founded the National Museum of Anthropology in 1875, a true temple to science, including a portico supported by columns. This doctor’s love for his profession was so strong he wanted to be buried in this very building. However, the curators mustn’t have considered the idea of a tomb in a museum to be very dignified, and in 1943 his remains were transferred to the San Isidro Cemetery to be buried alongside those of his wife and his daughter, who died after taking a laxative the he himself gave her to cure typhus.

The tale—told at many of Madrid’s literary debates and captured on paper by Ramón J. Sender, among others—tells of how the doctor embalmed her so he could continue treating her as though she were still alive. It’s said that sometimes an old saloon car could be seen passing by with its curtains drawn, in which the father and his deceased daughter travelled.

After this tour, there’s always time to head back to Madrid’s cemeteries and the Panteón de Hombres Ilustres, home not only to a valuable collection of funerary sculptures, but also to witnesses to Spain’s history carved in stone.