An LGBTIQA+ Art Walk

By Ignacio Vleming

Almost thirty years ago, in 1992, a crowd of people carried Cordoban artist Pepe Espaliú on their shoulders the length of the Paseo del Prado. The human chain bearing him along were taking part in a performance art piece entitled The Carrying Project that featured such well-known celebrities of the Movida movement as Alaska, Bibiana Fernández and Pedro Almodóvar. Before they reached the Reina Sofía Museum, they stopped in front of the Ministry of Health.

The purpose of this action was to call on the government to adopt measures to fight the HIV pandemic. Some months later, Espaliú, already ill at the time, died of AIDS. This journey, without touching the ground, was meant to represent an almost catatonic state, as he explains in one of his wonderful literary texts that have been compiled in La Imposible Verdad (The Impossible Truth) published by La Bella Varsovia.

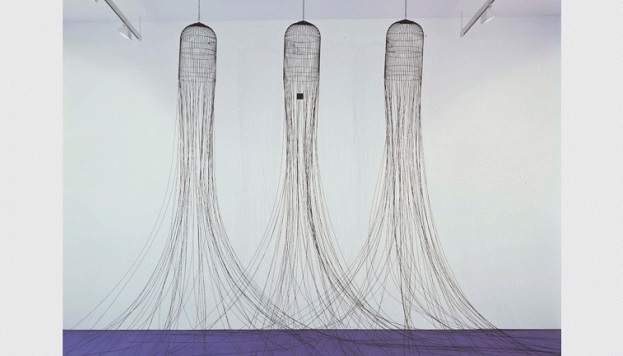

He also created a series of drawings and sculptures for The Carrying Project that are now part of the collection of the same museum before which the performance ended. Works that speak of pain, fear and death, but also of the need for beauty. Works that bring to mind another very important artivist (artist + activist) in the fight against HIV, David Wojnarowicz.

In 2019 the Reina Sofía Museum dedicated an exhibition to Wojnarowicz, organised in collaboration with the Whitney Museum of American Art. The Spanish museum’s permanent collection includes his series Arthur Rimbaud in New York – which reflects on the true identity of Rimbaud, the enfant terrible of French poetry and author of A Season in Hell.

Equally striking are the performance art pieces by José Pérez Ocaña, the artist whose career began in the 1970s when he left his village in Seville to conquer the Barcelona of the Divine Gauche movement. He inspired illustrators like his good friend Nazario, and filmmakers such as Ventura Pons and Gérard Courant, who filmed a performance art piece that he put on in front of the Brandenburg Gate in Berlin. This is also conserved in the museum, together with a handful of his self-portraits.

Another notable artist is Gregorio Prieto, who was strongly influenced by metaphysical painting and who produced a body of work in the 1950s which contained references to the gay imaginary, such as the symbolic photographs he took in collaboration with Eduardo Chicharro Briones.

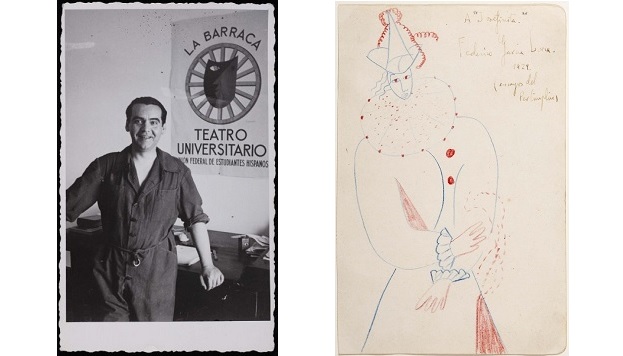

Also worthy of mention is the friendship between Federico García Lorca and Salvador Dalí, interpreted as a love relationship by various researchers, most notably Ian Gibson. The Reina Sofía houses several documents by the author of the Sonetos del Amor Oscuro (Sonnets of Dark Love) that have to do with the La Barraca theatre company, which is where he met Rafael Rodríguez Rapún. It also boasts a beautiful drawing inspired by his play Amor de Don Perlimplín con Belisa en su Jardín (The Love of Don Perlimplín for Belisa in the Garden).

The museum is also home to a collection of paintings by Dalí, including a Still Life which he painted in 1926 under the influence of Cubism.

Since 2017, when the World Pride was held in Madrid, the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum has been offering a full LGBTIQA+ tour that can be downloaded in PDF format and includes 16 works.

There are two particularly noteworthy paintings that allude to the new female identities that emerged during the 19th century. Horsewoman, Full-Face (L'Amazone) is a painting by Édouard Manet that was intended to be part of an unfinished series on the four seasons. The canvas in the collection represents summer, and on it Henriette Chabot poses in her riding gear, an outfit that gives her a certain masculine bearing. The “portrait” of Gertrude Stein by Charles Demuth also exemplifies this hall of mirrors.

We have one more stop left on the Art Walk. We could well be forgiven for mistakenly thinking that the Prado Museum, given its venerable age, is the museum least sympathetic to the queer imaginary. However, quite the opposite is true: the rooms in Villanueva's building, replete with mythological paintings, show that love between people of the same sex and non-binary identities are far from being a new phenomenon.

In 2017, also on the occasion of the celebration of World Pride in Madrid, Carlos G. Navarro mapped out an itinerary through the permanent exhibition that revealed to many of us the enormous wealth of the museum in terms of LGBTIQA+ diversity.

A good place to start is El Cid, the portrait of a fierce lion painted by the openly lesbian artist Rosa Bonhuer in 1879. A work that, together with La Siesta by Lawrence Alma Tadema was donated to the museum by art dealer Ernest Gambart, Consul General of Spain in Nice, in an effort to defuse the scandal surrounding his homosexuality.

From here we can journey into the past in search of some of the most outstanding gay icons. In this respect, the Baroque period offers such works as The Rape of Ganymede by Rubens, Ribera’s The Bearded Woman, in which Magdalena Ventura is portrayed with enormous dignity, and Saint Sebastian by Guido Reni, a painting that is very similar to the one that sexually arouses the protagonist of Yukio Mishima’s autobiographical novel Confessions of a Mask. The Prado Museum also houses a Caravaggio that portrays David with the Head of Goliath and a bronze cast of the Hellenistic sculpture Hermaphrodite. Displayed opposite Las Meninas, the sculpture was commissioned in Italy by Velázquez during the Spanish Golden Age.

The rooms dedicated to classical sculpture offer countless examples of sexual diversity, but our gaze inevitably turns to The San Ildefonso Group. The sculpture of two young men – one following the canon of Polykleitos and the other that of Praxiteles – who may well represent Orestes and Pylades, not only sums up ancient Greek art, but is also a hymn to the boys’ beauty.